Chasing Summer

With summer winding down in the northern hemisphere and days getting shorter faster, I started wondering: How far would I need to travel today to get the same length of daylight tomorrow?

To answer that question, we need to be able to approximate two things:

- Length of daylight at a given latitude on a given day.

- Distance from one latitude to another.

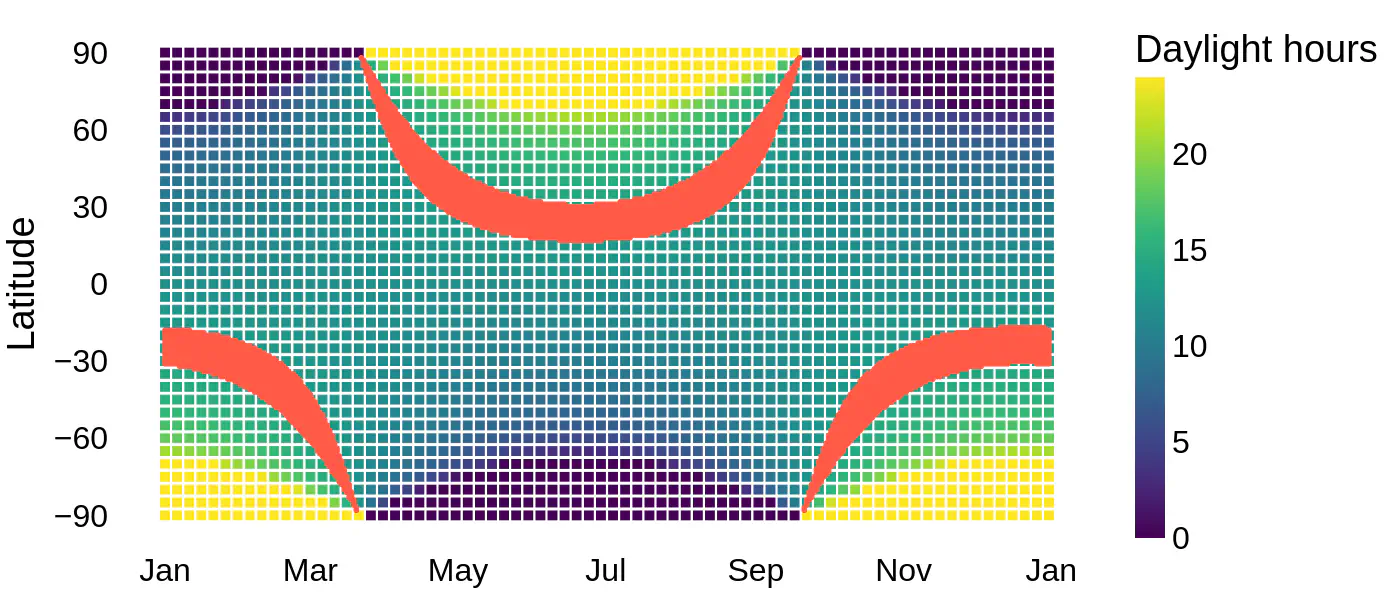

Day length throughout the year by latitude. The red band shows areas with 13.5 hours (± 30 minutes) of daylight year-round.

If you want to skip all the math and just get the answer at your location, here’s an interactive version.

Formulas and Functions

After fumbling my way through some very basic astronomy, I came up with the following Python functions to calculate daylight hours1 at a given latitude and day-of-year:

def _solar_declination(doy: int) -> float:

"""Calculate angle between the equator and sun in radians on a given day."""

return -0.409 * math.cos(2 * math.pi/365 * (doy + 10))

def _hour_angle(latitude: float, declination: float) -> float:

"""Calculate hour angle in based on latitude and declination in radians."""

x = -math.tan(latitude) * math.tan(declination)

# 24 or 0 hours of daylight

if x < -1:

return math.pi

if x > 1:

return 0.0

return math.acos(x)

def get_day_length(latitude: float, doy: int) -> float:

"""Return daylight hours at a given latitude in degrees and Julian day."""

lat_rad = math.radians(latitude)

declination = _solar_declination(doy)

ha = _hour_angle(lat_rad, declination=declination)

return ha * 7.639

They’re full of magic numbers and trig functions that I half remember, but they seem to produce reasonable answers, and don’t break when things get weird towards the poles.

Number of daylight hours by day of year (left) by latitude (right).

The only other thing we’ll need is a way to calculate the distance between two latitudes on a sphere2, which we can estimate with a simplified version3 of the Haversine formula:

def haversine_distance(lat1, lat2, radius=6371):

lat1 = math.radians(lat1)

lat2 = math.radians(lat2)

dlat = lat2 - lat1

a = math.sin(dlat / 2) ** 2 + math.cos(lat1) * math.cos(lat2) * math.sin(0 / 2) ** 2

c = 2 * math.atan2(math.sqrt(a), math.sqrt(1 - a))

return radius * c

Finally, we’re ready to pack up the car, crunch some numbers, and hit the road.

This Might Not Be Practical

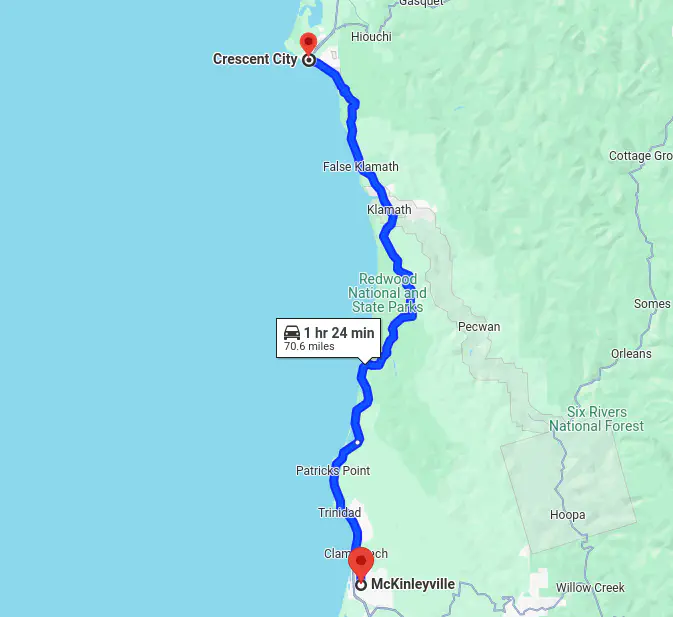

Today, August 23rd, I have about 13.5 hours of daylight at ~40.5° latitude. Tomorrow will be about 2.6 minutes shorter, unless I drive just 104 km north. That’s doable!

Close enough.

As we approach the autumnal equinox, things get tougher. By September 19, I’ve traveled 5,000 km in the last month to ~88° latitude, where I’m enjoying 13.5 hours of daylight just shy of the North Pole. But the next day is the real kicker.

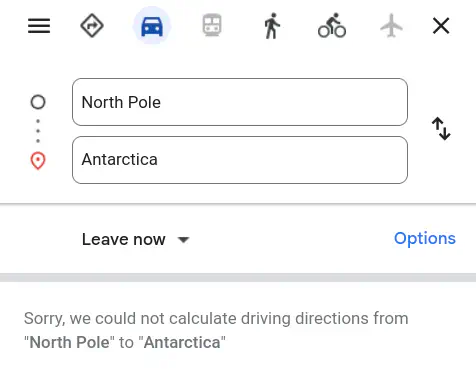

Having reached the North Pole and run out of extra daylight, it’s time for our longest travel day4: 20,000 km to the South Pole, where days are starting to get longer.

Still looking for an Airbnb, too.

Bonus Question

How fast would we need to travel each day to keep up with our 13.5 hours of daylight, assuming we devote 8 hours a day to travel?

- January: About 2 kph - an casual stroll.

- February: Ramping up to 10 kph - an easy bike ride.

- March 1 - March 21: Averaging 32 kph - an easy bike ride in the Tour de France.

- March 22: 820 kph - cruising speed of a 747.

If you’re curious, you can checkout out the analysis code here.

Approximately. Like all things in geodesy, getting 95% of the way to the right answer is pretty easy while the last 5% is brutally complex. ↩︎

Earth isn’t a sphere, so this is another convenient geodetic approximation. ↩︎

Who needs longitude? ↩︎

Tied with the vernal equinox, when we’ll need to make the opposite jump from the South Pole to the North Pole. ↩︎