Introducing AudioJPEG

As far as computers are concerned, images and audio are fundamentally just arrays of numbers: signals changing over time (audio) or space (imagery). That got me thinking about what would happen if we encoded audio data into an imagery format. What would it look like, and more importantly, what would it sound like if we can manage to decode it?

Enter AudioJPEG: The Worst Compression Algorithm™.

Encoding Audio

All we need to do to convert an audio file to an image file is:

- Load the audio as an array of numbers in the shape

(samples, channels). - Scale it1, pad it, and reshape it to fit in an image array of shape

(rows, columns, bands). - Write it out as a JPEG.

I won’t go into detail on the code since it’s mostly wrangling Numpy arrays, but I did run into one interesting decision during the reshaping.

Reshape Order

If you picture the samples in an audio file as a one long line of 60 square blocks, we’ll turn it into an image by rearranging those blocks to build a big cube that’s 4 blocks long, 5 blocks wide, stacked 3 blocks high (red, green, and blue channels).

Our blocks aren’t numbered, so we’ll need a repeatable strategy for what order we place blocks that we can reverse to recreate the original pattern. Numpy offers two options here: C order and Fortran order. C order places rows first, then columns, then repeats for the next layer. Fortran order builds stacks of 3 blocks, then arranges those into columns, and repeats that process for each row.

Either way will work, but it turns out that there are some interesting implications for compressed audio quality. JPEG compression works in chunks of pixels2, so each sample will be affected by the samples it’s grouped next to. C order is more likely to place samples that are close together in time next to each other, reducing audio artifacts. Fortran order looks cooler, so obviously that’s what I went with.

First Look

With our basic algorithm figured out, we can now turn this 30 seconds of audio…

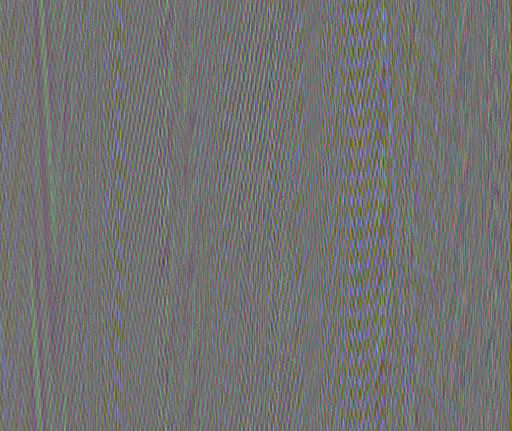

…into this 432 x 512 image:

Samples encoded into pixels in Fortran order.

Now we could reverse the process and turn our image back into audio, if it wasn’t for…

The Metadata

To decode an image without access to the original audio file, we’ll need to be able to store and retrieve metadata in the image. The original sample rate, number of samples and channels, and unscaled amplitude will all be necessary to accurately reconstruct our audio file.

If you’re thinking that there’s already a well-established way to store metadata in an image file using Exif, you’re right. But if we were looking for convenient, reliable solutions we wouldn’t be building The Worst Compression Algorithm™. So I encoded the metadata into a bit array that I tack on top of the image as an extra row of pixels3.

Encoding Metadata in a Header

Each metadata property is assigned a fixed number of bits, which are set based on the value of the property. For example, we encode the reshaping order into 7 bits representing the corresponding ASCII character4 C or F (Fortran). An image in Fortran order encodes the bits 1000110, which we set as pixel values in the top row of the image.

Encoding the rest of the metadata properties gives us 95 total bits, which for simplicity we’ll call the minimum image width. To try and limit metadata corruption5 during compression, I scaled the bits by 255 and stored a redundant copy in each band.

Decoding Images

Turning an image back into audio is now pretty straightforward. We need to:

- Load the image as an array of numbers in the shape

(rows, columns, bands). - Remove and parse the bits of the metadata header, averaging values across bands to compensate for compression artifacts.

- Reshape, remove the padded pixels, and rescale to the original amplitude.

- See what it sounds like.

What Does it Sound Like?

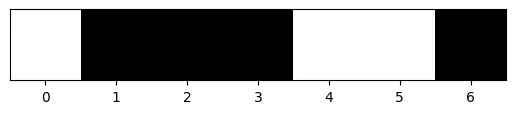

I encoded and decoded 3 different versions with different JPEG quality levels, along with a test image for a visual comparison of the compression level.

JPEG Quality 100

At maximum quality, the decoded audio sounds unchanged, apart from some very subtle background hiss.

|  |

JPEG Quality 50

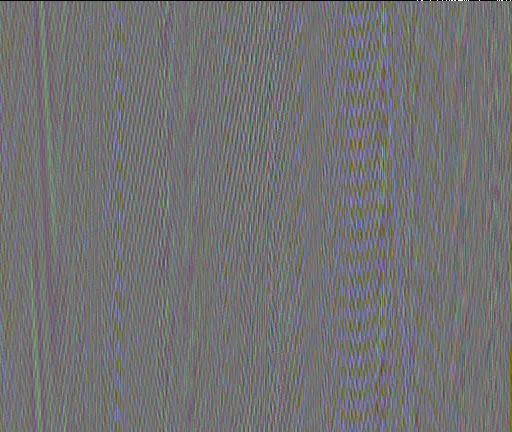

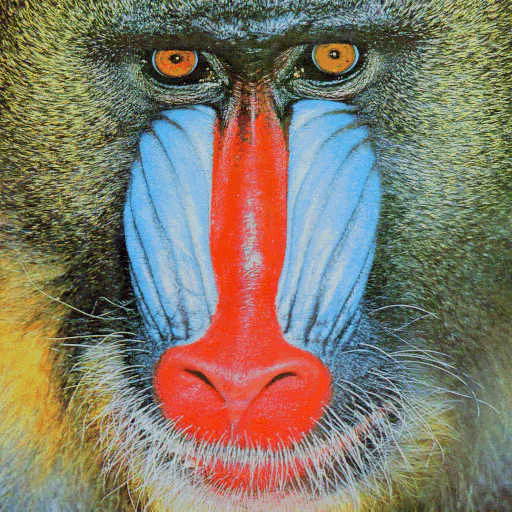

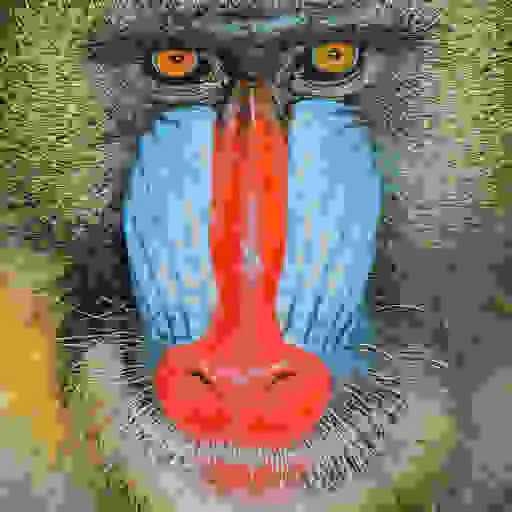

At the halfway point, the subtle hiss has turned into some much less subtle digital distortion. You can still make out the melody, but only just. Meanwhile, the test image looks nearly indistinguishable, even zoomed in.

|  |

JPEG Quality 1

Uh oh. The images alone make it pretty clear that this one is doomed, and as expected the audio sounds more like a broken dialup modem than music.

|  |

Volume Warning: This sounds awful.

On closer inspection, the metadata header has been obliterated by compression, leading to incorrect sampling rates and amplitudes. But somehow, manually entering the correct values doesn’t make it sound any better.

It looks like we’ve gone too far.

Compression Ratio and Quality

If we’re proposing a new compression algorithm, we’d better look at the compression ratio and compare with an existing standard like MP3.

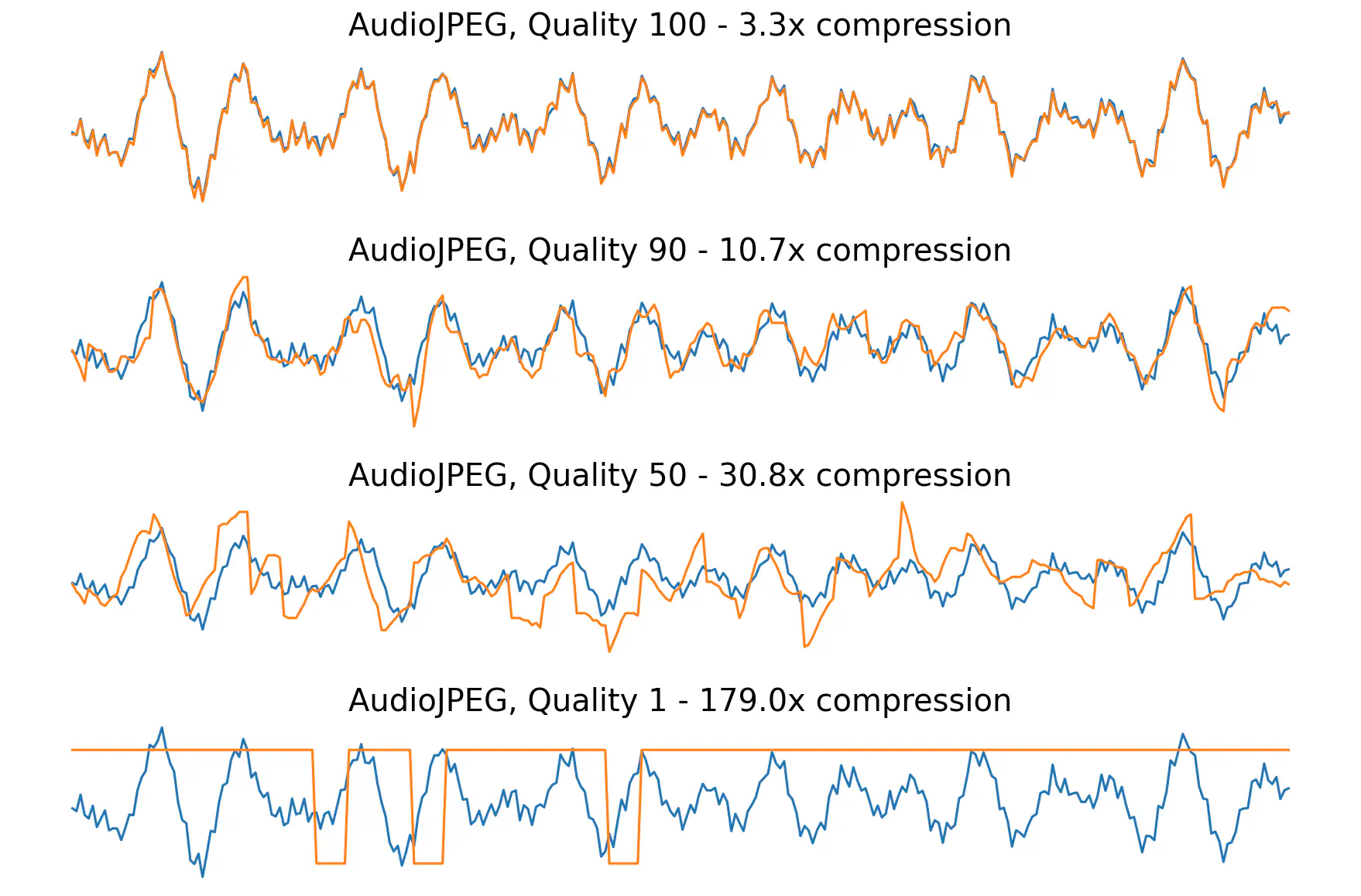

Below, you can see how well the compressed waveforms match the original at each quality level, starting with a very close approximation and ending with our dying fax machine6.

Original (blue) and compressed (orange) waveforms for different quality levels.

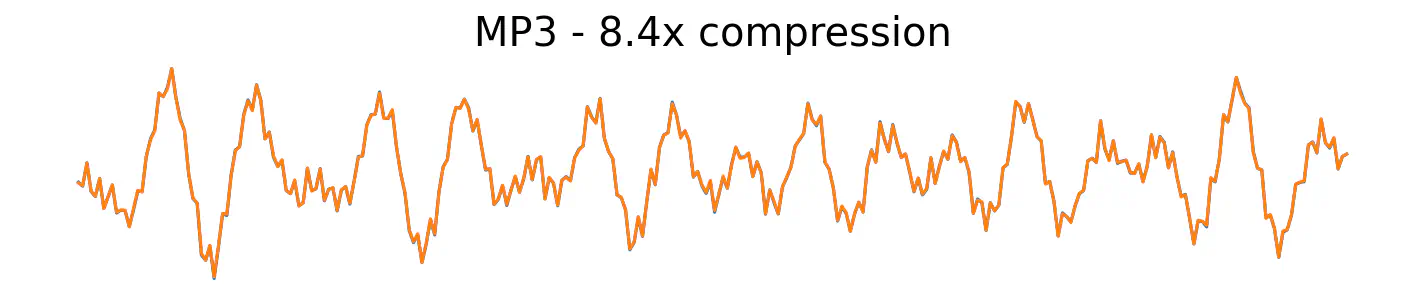

How does that compare with MP3? The compression ratio is actually pretty comparable.

Technically there are two lines here.

The audio quality is not.

Conclusion

Next up, VisualMP3?

Audio is natively stored in a wide variety of data types, but I’m focusing on 16-bit since that seems like a common standard for WAV files. We’ll need to compress that 8-bit to fit in a JPEG, so we’re going to lose some fidelity even before we introduce the compression. ↩︎

I highly recommend this video if you’re curious about how JPEG compression works. ↩︎

I read somewhere about an old video game that used a similar strategy by spilling game data from the limited RAM onto the screen where it would show up to users as mysterious colorful pixels. I tried to track down that source without any luck, so if it sounds familiar please let me know! ↩︎

We could save a few bits by encoding the index of the order from a lookup table instead of the order itself, but we’re not aiming for maximum efficiency here. ↩︎

I originally wanted to use steganography to store the metadata, which nudges pixel values even or odd to stealthily encode bits, but there was no way that would hold up to JPEG compression. ↩︎

I had to manually correct the corrupted metadata to get them on the same graph. ↩︎