Patch Metrics in Earth Engine

Area isn’t everything. Knowing how much old-growth forest, high-severity fire, elk migration corridor, etc. falls within your landscape is valuable, but often it only tells part of a story. Two fires might burn the same amount of forest, but if one torches a homogeneous swath across the landscape while the other disperses over dozens of small, disconnected patches, those forests will regenerate very differently.

Patch metrics quantify spatial patterns to provide a deeper understanding of where and how patches are distributed across a landscape. Tools like Fragstats, landscapemetrics, and PyLandStats allow for analysis of these metrics with local data, but what would it take to calculate them in the cloud using Earth Engine? In this post, we’ll walk the process of implementing some common patch metrics in GEE, allowing us to analyze landscape dynamics at regional scales.

⚠️ Warning: We’ll use the Fragstats definitions to build our metrics, but adapting the algorithms for Earth Engine will require different implementations that will produce different outputs. Results should be close in most cases, but be careful making comparisons between tools!

The Landscape

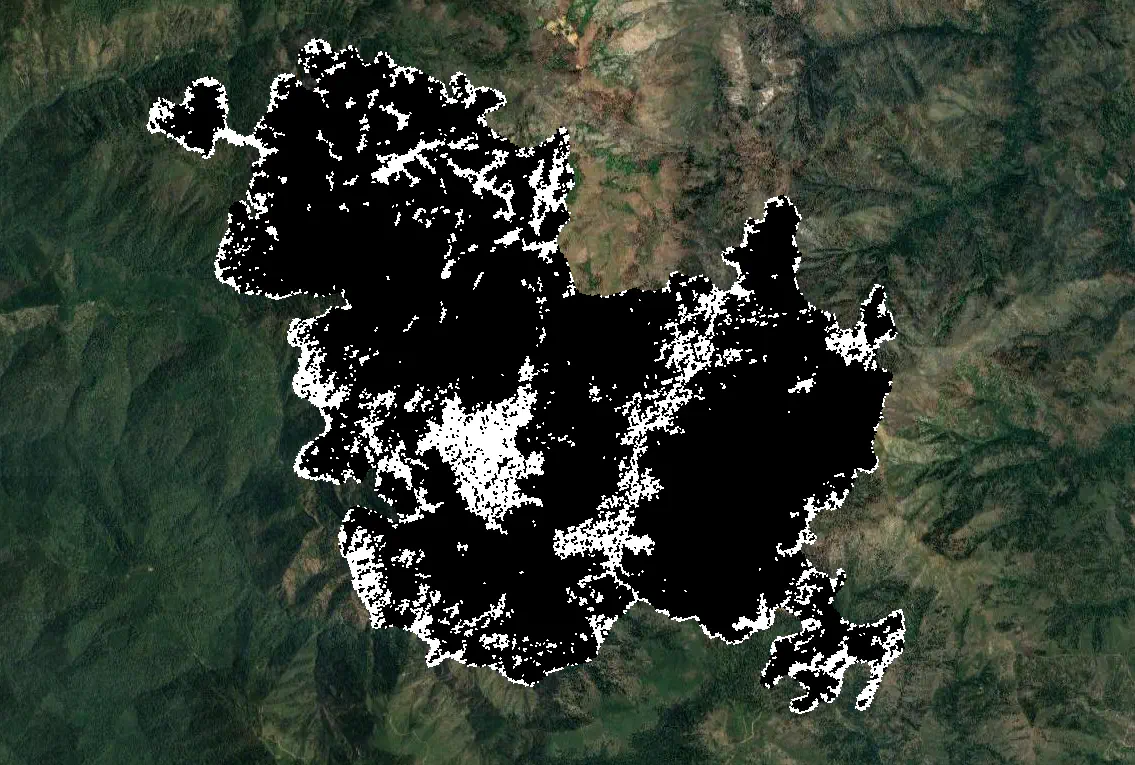

These algorithms will work with any categorical raster. For demonstration purposes, we’ll look at patches of unburned forest in the 2013 Corral Complex wildfire in Northern California. The arrangement of residual trees in a burned landscape affects seed dispersal and regeneration, making landscape metrics a useful tool for quantifying fire effects.

Our data source will be a map of burn severity from the Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity (MTBS), and we’ll consider “unburned” patches (class 1) as our class of interest.

var unburned = ee.Image("USFS/GTAC/MTBS/annual_burn_severity_mosaics/v1/mtbs_CONUS_2013").eq(1);

Patch Metrics

Getting the Patches

With our landscape defined, we can start turning that raster into a collection of patches. While raster-based approaches to landscape metrics in Earth Engine are possible (check out this talk by Noel Gorelick), achieving an output that’s comparable with other tools will always require converting images to features at some point in the process. To keep things simple, we’ll do it right at the start, using ee.Image.reduceToVectors to turn patches of contiguous pixels into polygons.

var bbox = ee.Geometry.Point([-123.4683, 41.0304]).buffer(6000).bounds();

var patches = unburned.selfMask().reduceToVectors({

reducer: ee.Reducer.countEvery(),

geometry: bbox,

crs: unburned.projection(),

eightConnected: true,

});

print(patches.size()) // 592

Note that we used selfMask to include only the unburned pixels and used eightConnected to allow diagonal connections (aka the Moore neighborhood or Queen’s case). The resulting feature collection contains 592 patches of unburned forest, ranging from single 30m pixels to large contiguous stands of residual trees. These features will be the basis for all of our metrics.

Area and Perimeter

We’ll start off with the easy metrics - area and perimeter.

/**

* Calculate patch area in hectares.

*/

function patch_area(patch) {

return patch.set({area: patch.area(1).divide(1e4)});

}

/**

* Calculate patch perimeter in meters.

*/

function patch_perim(patch) {

return patch.set({perim: patch.perimeter(1)});

}

patches = patches

.map(patch_area)

.map(patch_perim);

With a vector-based solution, these first metrics are trivial to calculate, but already they allow us to start quantifying the landscape.

print("Total patch area:", patches.aggregate_sum("area"));

print("Mean patch area:", patches.aggregate_mean("area"));

print("Largest patch:", patches.aggregate_array("area").reduce(ee.Reducer.max()))

Those 592 patches constitute 1,050 hectares of unburned forest. The largest patch is 167 hectares, but on average they are only 1.8 hectares in size.

Core Area

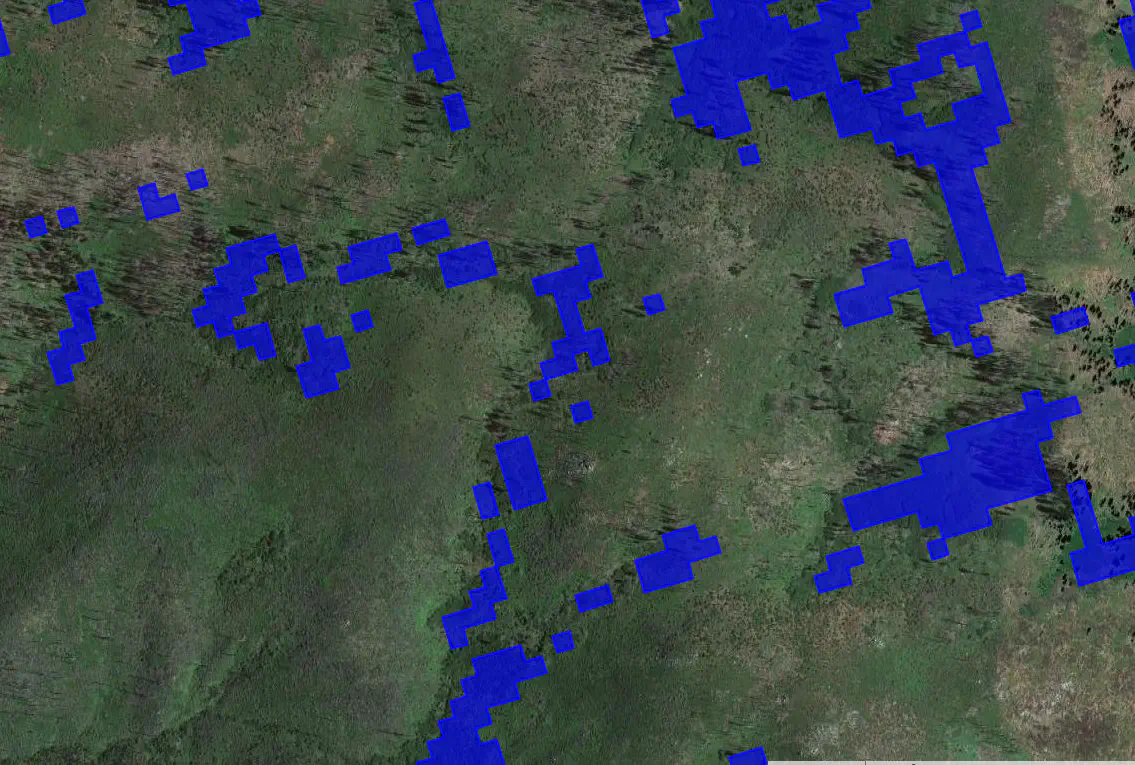

The habitat suitability of a patch may depend on more than just its size. While some wildlife species thrive in the margins between different habitat types, others requires large, homogeneous areas to nest and hunt. Core area describes the size of a patch after excluding edges, and we can calculate it by 1) using a neighborhood reducer to find pixels that border multiple cover types (i.e. the edge between burned and unburned patches), 2) masking those pixels in the original unburned map, and 3) calculating the area of the remaining core pixels. The first two steps are implemented below:

var edge = unburned.reduceNeighborhood({

reducer: ee.Reducer.countDistinct(),

kernel: ee.Kernel.square(30, "meters")

}).reproject(unburned.projection());

var core = unburned.multiply(edge.eq(1));

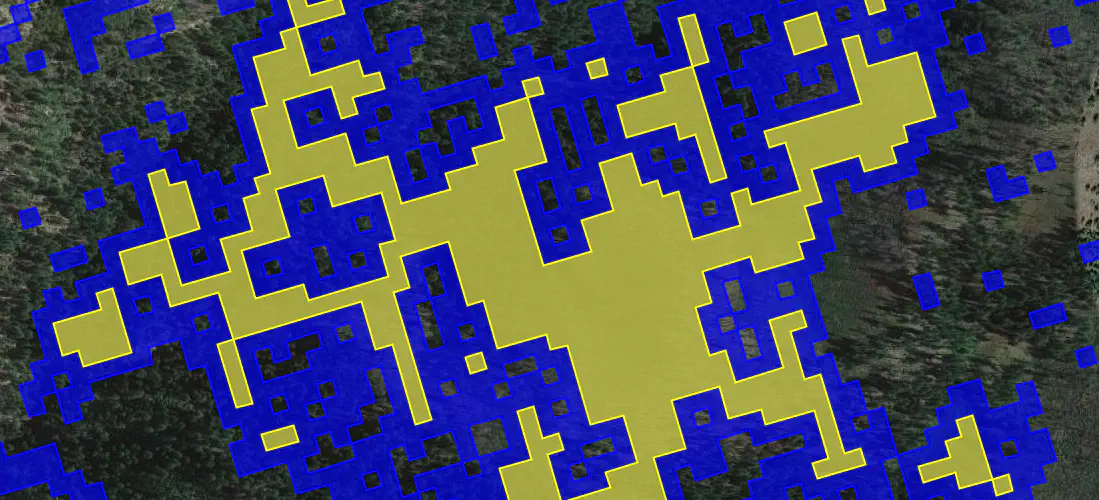

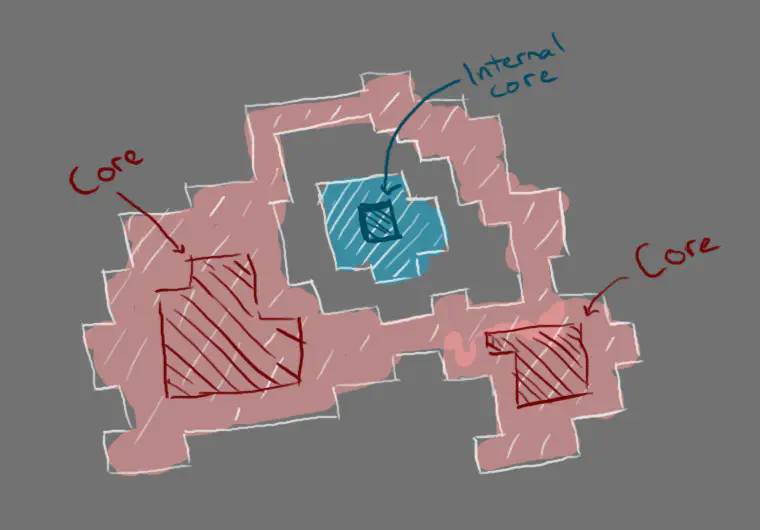

With our core patches mapped, we can just vectorize them and calculate their area, right? Not quite. We need to know the core area for each of our original patches, which poses a technical challenge - how do we select the core patches associated with each original patch? While a filterBounds seems like an obvious solution, if a core patch falls within a hole in an original patch, it will be incorrectly included as a core patch when it was never part of the original patch. The blue core in the drawing below was never part of the red patch, but would be incorrectly included in a geometric filter.

Instead, we’ll use a raster-based solution to get the area of each core pixel, and then sum those values within each original patch using reduceRegion. While we’re at it, we’ll also calculate the core area index (CAI), which is the core area divided by the total patch area.

/**

* Calculate core area in hectares.

*/

function patch_core(patch) {

var area = ee.Image.pixelArea()

.updateMask(core)

.reduceRegion({

reducer: ee.Reducer.sum(),

geometry: patch.geometry(),

crs: unburned.projection(),

})

.getNumber("area")

.divide(1e4);

return patch.set({"core": area});

}

/**

* Calculate core area index.

*/

function patch_cai(patch) {

var area = patch.getNumber("area");

var core = patch.getNumber("core");

return patch.set({cai: core.divide(area).multiply(100)});

}

patches = patches

.map(patch_core)

.map(patch_cai);

Shape Metrics

The complexity of a patch’s shape can impact both its suitability for different species and its vulnerability to disturbance. Shape metrics quantify patch shapes, from simple squares to complex, irregular polygons. Perimeter-area-ratio (PARA), shape index, and fractal dimension index measure patch complexity by comparing perimeter and area in different ways.

/**

* Calculate perimeter-area-ratio.

*/

function patch_para(patch) {

var area = patch.getNumber("area").divide(1e4);

var perim = patch.getNumber("perim");

return patch.set({para: area.divide(perim)});

}

/**

* Calculate shape index.

*/

function patch_shape(patch) {

var area = patch.getNumber("area").divide(1e4);

var perim = patch.getNumber("perim");

var min_perim = area.sqrt().multiply(4)

return patch.set({shape: perim.divide(min_perim)});

}

/**

* Calculate fractal dimension index.

*/

function patch_fractal(patch) {

var area = patch.getNumber("area").divide(1e4);

var perim = patch.getNumber("perim");

var frac = perim.multiply(0.25).log().multiply(2).divide(area.log());

return patch.set({frac: frac});

}

patches = patches

.map(patch_para)

.map(patch_shape)

.map(patch_fractal);

Euclidean Nearest Neighbor

The distance between patches can affect migration and seed dispersal. Euclidean nearest neighbor distance (ENN) describes the distance from each patch to its nearest neighbor. This one is pretty easy to calculate using the ee.Feature.distance - the only catch is that we’ll need to use feature indexes to make sure we don’t measure the distance between a patch and itself.

/**

* Calculate euclidean nearest neighbor distance in meters.

*/

function patch_enn(patch) {

var pid = patch.get("system:index");

var other = patches

.filter(ee.Filter.neq("system:index", pid));

var dist = patch.distance(other.geometry(), 1)

return patch.set({distance: dist});

}

patches = patches.map(patch_enn);

Contiguity

While core area is based on a binary assumption that every pixel is either edge or core, contiguity uses a more nuanced approach where the connectedness of each pixel is measured by looking at its neighbors. Patch contiguity can then be summarized based on the contiguity of all of its cells.

We’ll first pass a contiguity kernel over every cell, with weights assigned based on the distance of each neighbor from the cell center.

var contiguity_kernel = ee.Kernel.fixed({

weights: [

[1, 2, 1],

[2, 1, 2],

[1, 2, 1]

], normalize: false

});

var contiguity = unburned

.convolve(contiguity_kernel)

.reproject(unburned.projection())

.rename("contig");

Now we just need to calculate the mean contiguity of each patch and normalize it based on the number of neighbors.

/**

* Calculate patch contiguity.

*/

function patch_contig(patch) {

var contig_mean = contiguity.reduceRegion({

reducer: ee.Reducer.mean(),

geometry: patch.geometry(),

crs: unburned.projection()

}).getNumber("contig");

var contig = contig_mean.subtract(1).divide(13 - 1);

return patch.set({contig: contig});

}

patches = patches.map(patch_contig);

Other Metrics

There are other patch metrics that could be calculated in Earth Engine, and I encourage you to go try them out! The unique capabilities of Earth Engine mean that not every metric will be practical (or maybe even possible) to calculate on the platform, but metrics like radius of gyration, related circumscribing circle, and number of core areas should be possible with some creativity.

Once patch metrics are implemented, most class metrics can be calculated by simply aggregating a given metric for each class. Landscape metrics like contagion and interspersion and juxtaposition are a little more complicated, but should be possible as well. Maybe we’ll tackle them in a future blog post…

Until then, you can find and run everything shown here in the Code Editor.